ECOSAN

Ecosan emerged as an interesting concept to me when I was finding out more about attitudes towards human waste in Africa, and the part that it could play in combatting it water-sanitation woes. Jewitt (2011) very neatly summarizes Ecosan as an interesting, low-cost, community-based alternative currently being emphasised, and targets the use of human waste to address soil fertility decline and reduce poverty.

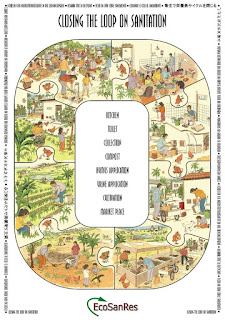

What exactly is Ecosan? Across studies, its definition holds the general description of recycling hygienized urine and faeces as fertilizers, subsequently using them in crop production. In doing so, the use of new, non-renewable resources would lessen, making it more sustainable option for sanitation and agricultural practice in Africa. Ecosan aims to utilize this as a systematic implementation of a material-flow-oriented recycling process (Wirbelauer et. al, 2003), where the goal is ultimately to return excreta to soils. It also promotes increasing crop production in rural areas, as well as to close ecological cycles of nutrients and organic matter (Esrey et. al, 1998 in Jiminez et. al, 2006) They saw this as an optimal option in addressing health, hygiene, sanitation and poverty problems (ibid), as Ecosan seemed like a good way to make use of human excreta in many daily household and economic activity.

Fig. 1: Poster on the Ecosan program (EcoSanRes, 2005)

Ecosan is considered a strong contender for sustainable sanitation due to its wide range of benefits in using human excreta. Studies by Dagerskog et. al (2008) on using Ecosan as fertilisers to increase crop yields in west Africa demonstrated its several advantages to the agriculture sector. Using Ecosan products often gave a higher yield during a longer harvest period, and in Saaba, it was also noted that the fruit had better quality and was more beautiful, albeit having no difference in actual taste. Hygienized urine and faeces yielded 30% more crops, and as resources, provided organic material, micronutrients and a slight increase in the soil pH (ibid). In places like Burkina Faso where the soil is of poor quality, this is strongly recommended for the improvement of soil structure. Human excreta is valuable because it contains organic matter, nitrogen and phosphorus (Jiminez et. al, 2006), though it must be noted that it has potential health risks due to possible pathogen content and that disposal is not regulated.

The use of either composting or dehydrating toilets and collecting their human excreta fertilizers might have been considered taboo to some communities, and some households were not accepting of direct reuse of urine or did not wish to undertake excreta-based composting (Salifu, 2001). However, many are increasingly convinced that Ecosan presents itself as a viable long-term option that was actually more aesthetically pleasant, and also eliminated problems of smell, flies and mosquito habitats whilst still protecting groundwater from pollution (Wirbelauer et. al, 2003). This became prevalent in Mozambique, and people were increasingly looking forward to using the compost to transform their yard and reap economic benefits. As people understand the ecological benefits of Ecosan, as well as the economic, high-quality benefits of their compost and crops, acceptance of the closed-loop system increased (ibid).

When introducing Ecosan to communities however, precautions have to be taken to ensure that it is also sustainable financially. Even though communities may like Ecosan for health and convenience reasons, there may be several economic issues surrounding a long-term, viable option for them. In South Africa, for example, it was found that this might require continuous access to funding to maintain momentum and maintenance on highly subsidized projects, and so subsidies in kind may be better (Wirbelauer et. al, 2003). However, with proper management of funding and where possible, it was found that acceptance of the closed-loop approach was higher in rural areas where people depended on agriculture and could easily see the added value of using the products, like in Zimbabwe. Other social and cultural factors must also be taken into consideration. Proper training to everyone in the family, not just the women, must be guaranteed to share the burden of sanitation, health and gardening (ibid). Proper training could also assist in technical problems, which might potential confuse and jeopardize the process if there is a lack of sufficient awareness of how the system works. In general, the introduction of Ecosan and the closed loop approach was much easier in places where there is a strong and long-standing culture of reuse, like in Zimbabwe where there was already a composting culture.

Ecosan clearly provides for a wide range of benefits, like preserving water for drinking, reducing the need for other chemical fertilizers, and the fundamental idea of taking advantage of the fact the an average adult produces 400-500 litres of urine a year, enough to plant nutrients to grow 250kg of grain (enough to feed one person a year)(Jewitt et. al, 2011), is something I find very intriguing . With the right combination of factors and careful planning and teaching of the approach, it can offer itself as a sustainable option for livelihoods and poverty alleviation. However, this system is unlikely to threaten the dominance of flush and discharge systems (ibid), which might be questionable in terms of what is actually a long term and viable solution for these countries.

I like this blogpost. You do well touch on some of challenges in sustaining Ecosan toilets and there is an interesting literature to explore more deeply about the challenges of scaling up different toilet/sanitation technologies.

ReplyDeleteDear Prof. Taylor,

ReplyDeleteThank you for reading my post, I'm glad you liked it!